Introduction

This article presents applied research and engineering on MEV (Maximal Extractable Value) activity in Ethereum, conducted entirely by me. It aims to provide transparency into MEV, quantify its impact, and highlight regional disparities, with a particular focus on Africa.

Inspired by DataAlways’s research on “The Geography of Block Building,” this work asks a central question: What is the state of MEV activity in Africa? The continent remains one of the most underrepresented regions in Ethereum block production, including validators, searchers, relay operators, and block proposers. Low validator activity, limited infrastructure such as bandwidth constraints, and scarcity of supporting resources have all hindered meaningful participation.

To address this gap;

-

I propose an FRP: GeoTAG: an opt-in on-chain metadata field included in the validator’s deposit or periodic consensus messages, representing a region or geocode claim about where the validator operator intends to run their infrastructure.

-

I developed Hirami: a data collection tool (still in active R&D) that monitors Ethereum mainnet activity, detects MEV using multiple heuristics, and optionally tags blocks proposed by African validators. This tool enables long-term MEV research, real-time observability, and Africa-focused analysis, providing actionable insights and supporting future participation from this region.

This article explores pathways to increase Africa’s engagement in Ethereum’s block-building ecosystem.

Scope and Constraints: This article focuses exclusively on MEV activity within the Ethereum network.

Motivation

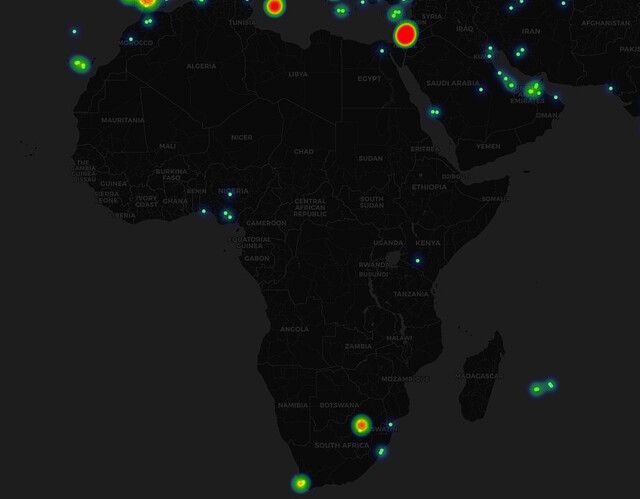

While exploring the Ethereum Network Topology Explorer, I was struck by a sobering reality: only a handful of green dots appeared on the Africa map, highlighting how little the continent currently contributes to Ethereum’s block-building ecosystem. This scarcity sparked a personal drive to dig deeper, understand the barriers, and find ways to help Africa gradually become an active participant in the global blockchain community.

Africa is, however, rapidly growing bit by bit. Initiatives like the Giga Validator in Rwanda, NodeBridge in Nigeria, and LaunchNodes across Africa are already laying the groundwork for a stronger Ethereum validator presence. On Solana, for example, Martin Tromp, founder of Superfast, has launched a validator in one of Teraco’s Johannesburg data centres, demonstrating that high-speed, scalable blockchain infrastructure is possible on the continent. Solana’s fast, low-cost platform serves as a proof point that Africa can host critical infrastructure for major smart contract networks and decentralized finance applications.

What motivated me further was the lack of publicly available MEV data from Africa. Without this information, it is difficult for African validators, researchers, and developers to understand the landscape or plan for growth. By building this Rust-based MEV monitoring tool, proposing GeoTAG, and conducting this research, I aim to create a foundation for the African Ethereum community, a resource that can collect and preserve data for years to come, whether that’s three, ten, or even twenty years.

This is more than research; it is a commitment to laying the groundwork so Africa can contribute meaningfully, sustainably, and visibly to the Ethereum ecosystem and the broader world of decentralized finance.

Around the Globe in MEV

“You can’t use an old map to explore a new world.” - Albert Einstein.

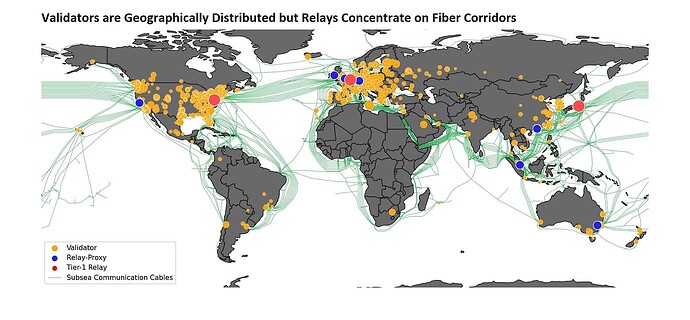

In Ethereum’s PBS ecosystem, geographic realities still shape how block production and sequencing occur. Proposers who outsource sequencing inherit the infrastructural and jurisdictional constraints of builders and relays, concentrating consensus power in certain regions. Mapping validator distribution, as done by Chainbound and the Ethereum Foundation, highlights these patterns and underscores how underrepresented regions like Africa remain largely untapped.

The global map reveals a stark contrast between validator locations and critical relay infrastructure. Validators, shown in orange, are fairly widespread: dense in North America and Europe, with notable clusters in East and Southeast Asia, smaller groups in Australia, and pockets in parts of South America. Africa and other inland regions remain sparsely represented, reflecting challenges like limited access to capital, cloud services, and reliable connectivity. Overall, the validator layer shows broad participation at the consensus edge, even as significant gaps persist.

In contrast, relays and tier-one relays, depicted in blue and red, are highly centralized and cluster along major subsea fiber corridors, primarily around the US coasts, Western Europe, East Asia, Singapore, and Australia. These locations mirror the global internet backbone rather than geographic diversity. For African validators, this concentration creates a structural disadvantage: interaction with the PBS ecosystem requires long-haul connectivity to distant relay endpoints, introducing persistent latency penalties.

As block auctions have become increasingly latency-sensitive, these geographic asymmetries matter. Validators operating from Africa must traverse transcontinental links to reach relay infrastructure, often competing against actors colocated near relay hubs. The result is a system that may appear decentralized in validator ownership, yet remains effectively centralized in transaction routing and block building. For Africa, this manifests as reduced competitiveness in MEV capture, higher operational risk, and increased exposure to relay-layer outages, reinforcing the continent’s marginal position in the MEV supply chain.

Case Study: Africa’s Position in the MEV Supply Chain

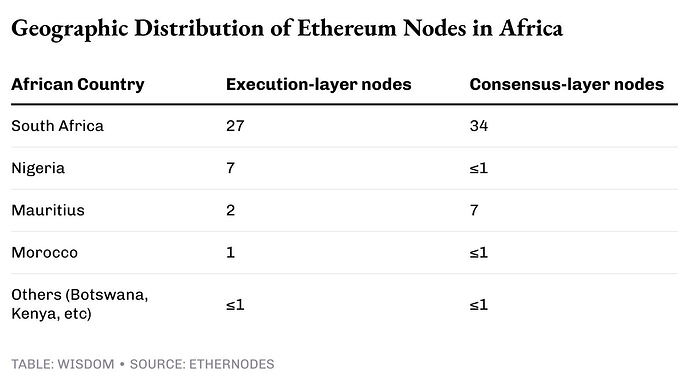

Focusing on Africa, validator infrastructure remains extremely limited. As of mid-2025, public node trackers report approximately 1.2 million validators globally according to UEEX, with African participation accounting for only a tiny fraction. For context, Public node trackers show very few execution-layer nodes in Africa:

Despite these challenges, interest in blockchain infrastructure across Africa is steadily rising. Countries such as South Africa, Mauritius, Morocco, and Nigeria lead the continent in crypto adoption. This raises an important question: for a continent of over 1.5 billion people (Worldometer), why does MEV-related activity remain so low?

Research conducted by the Zambian Open University helps contextualize this gap, summarizing the constraints into three core factors:

-

Limited Technological Access: Participation in Ethereum’s MEV ecosystem is highly sensitive to network reliability, latency, and hardware capacity. Across Africa, internet penetration averages around 37%, with high data costs and inconsistent connectivity further limiting sustained online engagement. Survey findings indicate that 56% of respondents perceive internet costs as prohibitive, while 45% lack smartphones or computing devices capable of running data-intensive Ethereum tooling, such as execution clients, MEV searcher infrastructure, or real-time monitoring dashboards.

Even in regions with relatively higher connectivity, frequent power outages and fragile infrastructure disrupt uptime. For validators and MEV participants, these interruptions translate directly into missed slots, degraded relay connectivity, and reduced competitiveness in latency-sensitive block auctions. As a result, African participants are structurally disadvantaged in Ethereum’s MEV supply chain, where milliseconds often determine profitability. -

Regulatory and Policy Uncertainty: MEV participation also operates within a fragmented and uncertain regulatory environment. While countries such as South Africa have begun articulating clearer guidelines for crypto assets and staking activity, others, including Nigeria, have periodically restricted crypto-related transactions in an effort to shield domestic financial systems from perceived instability.

For Ethereum validators, searchers, and infrastructure operators, this uncertainty raises operational risk. Running MEV-aware infrastructure often requires access to exchanges, RPC providers, cloud services, and cross-border capital flows, all of which can be disrupted by abrupt policy changes. Interviews with policymakers suggest that 72% would be open to regulatory sandboxes or pilot programs if provided with reliable data and risk assessments. However, the absence of harmonized regulation across African jurisdictions continues to impede long-term investment in Ethereum validator and MEV infrastructure. -

Cultural and Social Factors: Ethereum’s MEV ecosystem assumes familiarity with decentralized trust models, cryptographic guarantees, and adversarial market dynamics, concepts that may conflict with prevailing social norms in many African contexts. In societies where trust is traditionally mediated through community relationships and known intermediaries, systems that replace human trust with protocol rules can appear abstract or inaccessible.

Language barriers, religious considerations, and gender disparities further shape participation. MEV tooling, documentation, and research are overwhelmingly produced in English and assume prior technical literacy. In some regions, exposure to validator operations, block building, or MEV research is concentrated among a narrow demographic, limiting broader participation in Ethereum’s infrastructure layer.

Because of this constraint, there is effectively no public data on MEV activity originating from Africa. After countless hours of analyzing the Beacon API and related datasets. I found nothing that could reliably attribute MEV activity to the region, highlighting just how invisible African participation remains in today’s MEV data landscape.

To move beyond qualitative observation and begin addressing these structural gaps, this case study introduces Hirami and GeoTAG: a set of tooling and accompanying research designed to make Africa’s position in the MEV supply chain measurable.

Hirami

Hirami is an MEV data collection and analysis system designed to study Ethereum’s MEV dynamics. Its core objective is to address a more fundamental problem: the absence of reliable, geography-aware MEV data for African validators. Without such data, Africa’s role in Ethereum’s block production and value extraction pipeline remains largely unobservable, reinforcing the perception that MEV activity on the continent is negligible rather than under-measured.

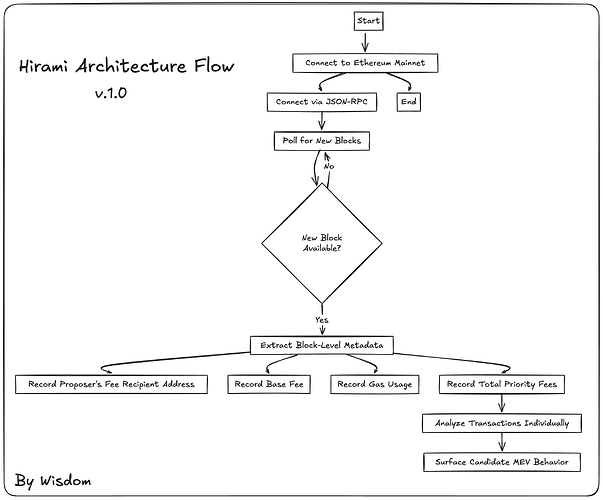

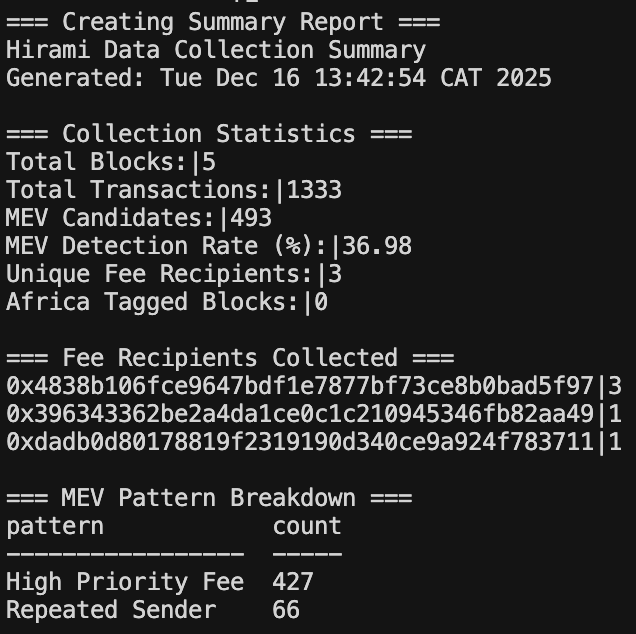

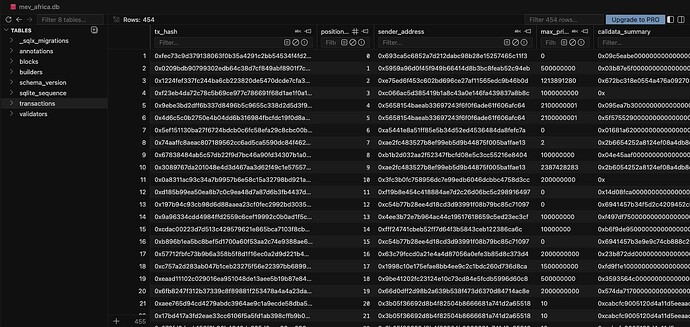

At its core, Hirami functions as a continuous ingestion pipeline that processes Ethereum mainnet blocks in real time. It connects directly to an execution-layer node via JSON-RPC (ChainStack), polling for new blocks at slot cadence and extracting block-level and transaction-level metadata. For each block, Hirami records the proposer’s fee recipient address, base fee, gas usage, and total priority fees, providing a granular view of value distribution at the execution layer. Transactions within each block are then analyzed individually, allowing the system to surface candidate MEV behavior rather than relying on aggregate fee signals alone.

MEV detection in Hirami is heuristic-driven. Instead of attempting full semantic classification of all MEV strategies, the system focuses on identifying structural indicators of extraction that are observable from execution-layer data. These include transactions with abnormally high priority fees relative to the block median, repeated sender patterns that suggest coordinated execution. Each detected pattern is stored alongside explicit reason codes, preserving interpretability and enabling downstream validation or refinement.

A defining feature of Hirami is its core focus on validator geography, specifically the identification of African-operated validators. Ethereum does not natively expose geographic metadata for validators, and fee recipient addresses are neither standardized nor publicly labeled by region. To address this, Hirami introduces an Africa-tagging layer that maps known validator fee recipients to operator metadata sourced from off-chain research, community contributions, and manual verification. During block processing, any block whose fee recipient matches an entry in this mapping is tagged as Africa-associated, enabling region-specific analysis without altering core ingestion logic.

This is where GeoTAG becomes instrumental. Hirami’s current approach hints at a natural evolution toward on-chain geographic commitments, and GeoTAG provides a conceptual foundation for this. GeoTAG is an opt-in on-chain metadata field that allows validators to self-declare their operational region.

By moving Africa-tagging and similar regional analyses on-chain. GeoTAG would increase reliability, auditability, and scalability, while still respecting privacy. Hirami is designed to integrate with such a mechanism in the future, but for now, it continues to operate with off-chain validator mapping and retroactive tagging.

The main limitation Hirami faces is informational rather than technical. The primary bottleneck in Africa-focused MEV research is the lack of publicly verifiable validator metadata. Hirami avoids inferring geography from latency, IP addresses, or transaction behavior, as such approaches carry significant ethical and methodological risks. Instead, Hirami plans to rely on explicit mappings derived from community engagement, beacon-chain metadata where available, and manual research into known African staking operators. While this constrains coverage in the short term, it preserves the integrity of the resulting dataset.

In practice, Hirami should be understood as a measurement infrastructure, not a complete picture of African MEV activity. Its value lies in making Africa legible within Ethereum’s MEV research ecosystem by establishing a repeatable, auditable data pipeline. In doing so, it provides a solid empirical foundation for future work, whether that involves economic analysis, infrastructure decentralization efforts, or policy discussions around validator participation in Africa’s markets.

The deployed version of Hirami is available on GitHub, and I welcome collaboration from the Flashbots team and other engineers to further develop it and enable robust tracking of MEV data.

GeoTAG

Ethereum’s geographic decentralization, the distribution of validators across diverse regions, is a key dimension of the network’s resilience, censorship resistance, and global fairness. Although Ethereum’s consensus protocol is agnostic to physical location, real-world deployments are heavily concentrated in a few regions with favorable latency and infrastructure, as seen above.

Recent research highlights how latency incentives in proposer-builder separation (PBS) and block building auctions have led to validators and builders clustering near major relays (e.g., U.S. East Coast, Western Europe), centralizing the MEV supply chain and weakening geographical diversity.

Validators in remote regions, including Africa, Latin America, and parts of Asia, face systemic disadvantages due to latency, limiting their economic competitiveness and visibility within the protocol’s decentralization metrics. Yet, the protocol today does not record or expose geographic metadata on-chain. Efforts to measure validator distribution rely on external network scans, telemetry, or third-party inference that cannot be cryptographically verified.

This proposal introduces a geo-commitment mechanism, GeoTAG, enabling validators to optionally commit a verifiable location claim on-chain. This mechanism would help the community understand and track genuine geographic diversity metrics, empower tools and dashboards to showcase global validator distribution, and inform future protocol and incentive designs that strengthen geographic decentralization as a first-class public good.

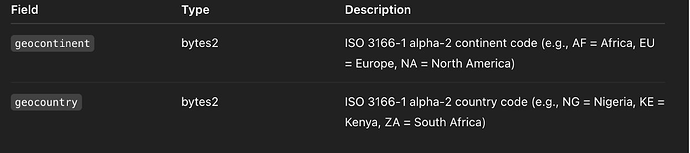

GeoTAG introduces two optional metadata fields for validators:

GeoTAG leverages zero-knowledge proofs to let validators prove their geographic location without revealing it directly. Each validator commits to their operational location privately and generates a proof that their location lies within a pre-defined, allowed region (e.g., Africa, South Africa, Europe).

- During registration, the validator submits this proof to the network. The actual coordinates of the country remain hidden, but the network can verify that the location is valid.

- Validators can update their location at epoch granularity by submitting a new proof signed with their validator key, ensuring continuous verification without exposing precise details.

- All proofs are recorded on-chain, creating a verifiable, auditable history of geographic commitments.

- The system prevents validators from falsely claiming to be in a region, while fully preserving privacy regarding exact location or network setup.

By using zero-knowledge proofs, GeoTAG provides strong privacy guarantees while still enabling the network, researchers, and other participants to verify regional diversity and ensure geographic decentralization of validators.

#newValidatorData

validator_registration:

pubkey: BLSPubkey

withdrawal_credentials: bytes32

signature: bytes96

geotag: bytes2 # 2-byte ISO code or region identifier

#epochlyProofOfIntent

geoupdate_body:

validator_index: uint32

new_geotag: bytes2

epoch: uint64

signature: BLSSignature

Let’s End it Here

Hirami’s existing Africa-tagging infrastructure is designed to complement and eventually integrate with GeoTAG. Currently, Hirami relies on off-chain mappings of validator fee recipients to manually verified geographic metadata, tagging blocks retroactively when African validators are identified. Once GeoTAG is widely adopted, Hirami can directly query on-chain geographic fields to identify Africa-associated blocks, eliminating the need for manual or community-provided mappings.

This integration would make Africa-focused MEV analysis fully auditable and scalable, while also enabling the system to track validator distribution globally. By building Hirami with GeoTAG compatibility in mind, the platform positions itself to transition seamlessly to an era of verifiable on-chain geographic data, enhancing the accuracy, transparency, and scope of regional MEV research.

I’m so happy to be working on Hiram & GeoTAG! I’m 19, and building a tool like Hirami that could help Flashbots engineers and researchers track validator geography is fascinating. I truly believe it can make a meaningful impact if guided properly.

What’s even more thrilling is how scalable and adaptable Hirami is; its modular architecture allows the Africa-focused tagging and MEV analysis framework to be extended to any region, anywhere in the world. GeoTAG as an FRP isn’t just a measurement tool; it establishes a repeatable, auditable pipeline that grows alongside Ethereum’s validator landscape.

Seeing this vision take shape and knowing it can empower regional research, improve transparency, and strengthen geographic decentralization genuinely fills me with joy and motivation.

what’s left:

→ Finish working on Hirami while asking for guidances

→ Extensive research on GeoTAG to propose it as an FRP

Official Github Repo for Hirami