Here’s an insight about the physical limits of MEV distilled into a short parable. The moral of the story is that to get the most benefit from acting on combined information, it may be necessary to commit not to acting on partial information, even when the latter is available more timely. There’s a fundamental exclusivity here: the authority to act on the information can’t reside in both places at once.

In a bustling industrial town, there were two factories, Factory A and Factory B, each producing a crucial component for a popular gadget. The town also had a central market where traders would gather to buy and sell shares in these factories based on their production output.

Two rival trading firms, Firm A and Firm B, each had a pair of traders: a junior trader known for their speed, and a senior trader renowned for their wisdom and negotiation skills.

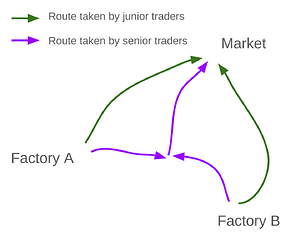

Every day, as the factory whistles blew to signal the end of the production shift, the junior traders would dash to the fastest train, the Green Line, racing towards the market. They carried with them the day’s production figures from their respective factories.

The senior traders, however, would leisurely board the Purple Line, a slower train that took a scenic route to the market. Interestingly, this train had a special carriage where the senior traders from both firms would meet.

Now, the junior traders, despite their speed and eagerness, were bound by a peculiar company policy. Upon reaching the market, they were not allowed to trade immediately. Instead, they had to wait for their senior colleagues to arrive on the slower train.

This policy often frustrated the junior traders. “Why must we wait?” they would grumble. “We have valuable information that could make us a fortune if we act now!”

Little did they know, something important was happening on that slow train.

In the special carriage, the senior traders from Firm A and Firm B would engage in intense negotiations. They knew that while their individual factory information was valuable, combining it could reveal insights far more precious.

However, these negotiations were delicate. Neither senior trader wanted to reveal their information without assurance of how it would be used. They needed time to build trust, to bargain, and to strategize.

One day, a wise old trader explained the situation to the impatient juniors:

“Imagine Factory A had a great day, but Factory B struggled. If you both traded on this partial information, Firm A would buy, and Firm B would sell. But what if the combined information showed that the struggles at Factory B would soon affect Factory A? By waiting for your seniors to negotiate and combine their knowledge, you might both decide to sell, avoiding a costly mistake.”

He continued, “The senior traders only engage in these valuable negotiations because they know you won’t act on your partial information. If they thought you might trade early, they’d rush to the market too, and we’d lose the chance to make better-informed decisions.”

The junior traders began to understand. They realized that their waiting allowed for a deeper, more strategic approach to trading. By holding off on immediate action, they were enabling a process that could yield far greater rewards.

From that day on, the junior traders waited patiently at the market, knowing that the slow train was bringing not just their senior colleagues, but a wealth of carefully negotiated, combined wisdom that would lead to more profitable trades for both firms.