In ‘Moving Away from aTLS’ difficulties with the aTLS protocol were discussed, as well as the desired requirements for a protocol for secure communication with a CVM-based service. But aTLS is just one of many different approaches to combining remote attestation with TLS. This post looks at how approaches to remote attested TLS have changed over time, discusses standardization efforts, and presents important design tradeoffs.

What is Remote Attested TLS?

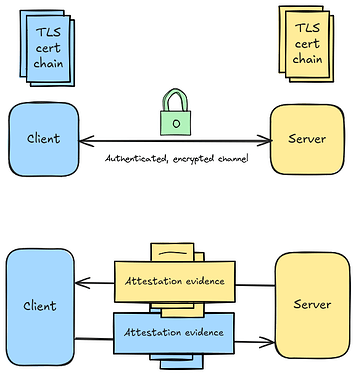

Remote attestation is a key component in confidential computing, allowing us to verify confidential workloads. But alone it provides only the ‘what’ but not the ‘who’.

Generally we want a way to bind an attestation to a remote party, such that we can be sure that we are communicating with, and only with, the party who provided evidence for the attestation. Often this is done by including a public key as input data to the attestation, and then using the associated keypair when authenticating with the remote party. Because the CVM issuing the attestation generates the key locally and never exports it, which can be verified through the measurements, only the actual CVM has access to the private key and we can be assured we are communicating with the expected party.

Since TLS is the standard protocol for secure internet communication, combining TLS with remote attestation seems like an obvious choice. But they can be combined in many different ways with different tradeoffs.

Early approaches using TLS certificate extensions

Probably the most influential and early versions of Remote Attested TLS is the defined in the 2018 paper ‘Integrating Remote Attestation with Transport Layer Security’ from Intel. It was designed for SGX, but the protocol can be generalized to any confidential compute platform, and the pattern quickly became adopted. For example Gramine RA-TLS, RATS-TLS, Open Enclave Attested TLS, SGX SDK Attested TLS, and of course Edgeless systems’ aTLS.

Eventually in 2023, the Confidential Computing Consortium’s ‘Attestation Special Interest Group’ made a standardization effort based on the protocol from this paper - see their post on Unifying Remote Attestation Protocol Implementations.

Although the original RATLS Intel paper prides itself on not requiring a specialized implementation of TLS, it does need specialized TLS certificates which most certificate authorities will not sign. Even if certificate authorities were to adopts this, needing to get them to sign the certificate on a per-attestation basis is impractical, as it makes it hard to incorporate custom input data without waiting for the CA to endorse a new certificate. This causes many implementers to use self-signed certificates.

How important are CA-signed TLS certificates?

Not being able to use certificate-authority signed certificates significantly restricts how protocols like aTLS can be used. This makes it appealing to switch to a protocol which allows us to use regular CA-signed certificates rather than self-signed ones. But it is important to be clear about what the advantages and limitations of this are.

Importantly, using a CA-signed certificate does not mean that once the certificate from example.com has been provided in a valid attestation, we can assume that subsequent connections to example.com can be considered attested. A single domain can have multiple certificates, so we still need to check that the public key in the certificate provided in non-attested sessions matches that from an attested session. From that point of view, it does not make the client’s life much easier - we still need to keep track of public keys.

What it does show, is that the entity who controls the domain name chose to endorse this remote party at the point at which the certificate was generated - by adding a DNS record which resolves to to the IP of this service. Furthermore, using CAA records it is possible bind the domain to a specific ACME account which is much more specific than an IP address - see dStack’s zero-trust HTTPS protocol, section 3.3.1.

Certificate authorities have techniques of checking DNS resolution which are generally stronger than if we did a DNS resolution ourselves, for example by checking from multiple locations. So its like an additional guarantee that we have a thumbs-up from the domain name owner.

Later approaches using TLS handshake message extensions

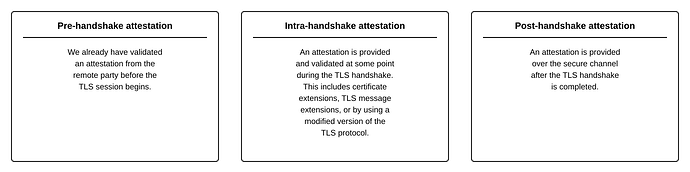

The lack of CA endorsement and difficulties with using fresh attestations on a per-session basis led to a new paradigm which got around this problem. Custom data can be transferred in the handshake without modifying the certificate or the TLS protocol by using TLS handshake message extensions.

This new pattern quickly spurred new developments, for example the 2022 Weinhold-RATLS paper, and an IETF draft for a standard based on this approach was proposed (draft-fossati-tls-attestation), with nine iterations of the draft between 2022 and 2025.

Probably the most advanced form of this approach is defined in the 2025 paper ‘Separate but Together’. In this design, Diffie-Hellman context material from the handshake is included in the attestation, to bind it to the session. However, popular TLS implementations (eg: OpenSSL) do not provide a way to access this, meaning a modified TLS library needs to be used, making it difficult to implement.

Furthermore, sending the attestation before the TLS handshake is finalized means that it is not transmitted over a fully authenticated channel, and although we can include handshake data as input to the attestation, it is still not bound to a fully authenticated channel, since not all handshake data can be included until the handshake is complete.

Recent proposals using post-handshake attestation

Providing the attestation after the TLS handshake means that we have all the guarantees which TLS provides when the attestation is made, and no special TLS implementation or special certificates are needed. This is a big advantage as it makes it easy to implement the protocol in a way which caters for both remote-attested-TLS-aware connections and naive clients using regular TLS.

TLS thankfully offers a way to export keying material from the session (RFC5705), making it possible to bind an attestation to a fully authenticated session by providing the exported keying material as input data to the attestation. This is a way of showing that the attestation came from the remote peer, and was not copied from another machine.

Based on this, authors of the IETF draft proposed a new draft, draft-fossati-seat-expat - ‘Post Handshake Attestation using Exported Authenticators’. The design combines two other IETF standards in order to present attestation evidence in a standardized way. TLS exported authenticators (RFC9261), which define a standardized way to present data which is bound to the session. and RATS Conceptual Message Wrappers, which is a platform-agnostic way to present attestation evidence (also currently in draft).

This approach has some significant security advantages. But since it is a draft standard which is based on other draft standards, endorsing it right now exactly as it is written adds quite some complexity. Perhaps the standard is not mature enough to fully adopt at this stage, but the underlying principle of post-handshake attestation using exported keying material from the session is very promising.

Attested TLS certificate or attested TLS session?

Whether to bind the attestation to this particular session, or to the TLS certificate, is an important design decision.

By including the TLS long-term key from the leaf certificate as input for attestation, one can guarantee that the private key was generated in the CVM, provided the CVM software image does not allow any way of importing or exporting it. This means that subsequent TLS sessions which use the same certificate can be considered to be attested, without needing to wait for an attestation to be generated and verified.

Stronger still is attesting the TLS session, where key material from the current session (which includes ephemeral handshake data unique to the session) is used as input to the attestation. This guarantees freshness of the attestation and binds it to this particular channel, making it hard for an attacker to modify the CVM state without breaking the connection. The downside is that we need to do attestation generation and verification per-session, which in some circumstances adds an unacceptable amount of time. Furthermore the client is required to compute the ‘exporter’ (retrieve key material from the TLS session). Although this is defined in RFC9266, many HTTPS clients and client libraries do not offer this functionality out of the box.

To get the best from these trade-offs, a promising solution is to use both. Having 64 bytes of quote input data means one can use 32 bytes for the TLS certificate public key hash and 32 bytes for a session exporter. The remote party can choose whether to verify just the public key, or both the public key and the session exporter.

Conclusion

Development of remote attested TLS protocols has come a long way. Although they generally remain best suited to server-to-server communication, the special requirements for client verifiers can be greatly reduced.

Post-handshake attestation together with TLS channel binding offers some promising advantages over other approaches. But for some use-cases, requiring client-side computation of the channel binding is impractical. By including both a channel exporter and a TLS certificate public key in an attestation, the attestation is still useful to clients who are unable to do this.

A protocol together with an implementation are in active development which incorporates these ideas in the context of Flashbots’ use-cases. This post has covered the high level design decisions being explored. Details of exactly how the attestation exchange is presented over the channel will come later.