This post was originally posted on 2022-01-16

Author: Xinyuan Sun, @sxysun

Speeding up the Ethereum Virtual Machine (part 1)

Thanks to Alejo Salles, Hongbo Zhang, Alex Obadia, and Kushal Babel for feedback and review of this post.

With a more performant Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM), we can achieve better network scalability and more efficient maximal-extractable-value (MEV) extraction. This series of posts analyzes several approaches to speed up the EVM with a focus on parallelization and shared data conflict analysis.

TLDR:

Ethereum Virtual Machine(EVM)'s performance is vital for several reasons. First, if we have a faster VM then Ethereum clients will be able to process and verify transactions faster, thus making it easier for everyone to run a full node and strengthening the decentralization and security of the network.[1] Second, as MEV extraction on Ethereum becomes more prominent, we need to make MEV extraction easier so profits from it can be more evenly distributed to prevent economic centralization of the network. A more performant EVM achieves this by helping searchers (and block builders when Ethereum introduces Proposer-Builder Separation) to produce more profitable full blocks and relays to have better latency. This means the builder market will become more efficient, thus attracting more searchers and making the market even more competitive, which in turn makes it more difficult for people to do reorgs that endanger network stability.

To improve EVM performance with backward compatibility and minimal change to consensus rules or how storage is implemented, we need parallelism.[2]

In part 1 of the series, we argue the need for a parallel EVM and cover general approaches to achieve it such as EIP 648, EIP 2930 and speculative execution. In part 2 we study how static analysis and formal methods can make the EVM parallelizable, specifically we present two simple algorithms for achieving parallelization.

Background

Decentralization is vital to blockchain security: it is hard for participants in a decentralized network to collude. Ideally, this is achieved by as many individual parties as possible running nodes to verify ongoing transactions. However it usually takes more than 3 days for regular users with a personal computer to spin up a full node on Ethereum (it requires days to re-compute and validate the 13 million blocks out there). Behind this inefficiency is Ethereum’s large storage size and more specifically EVM’s storage design:

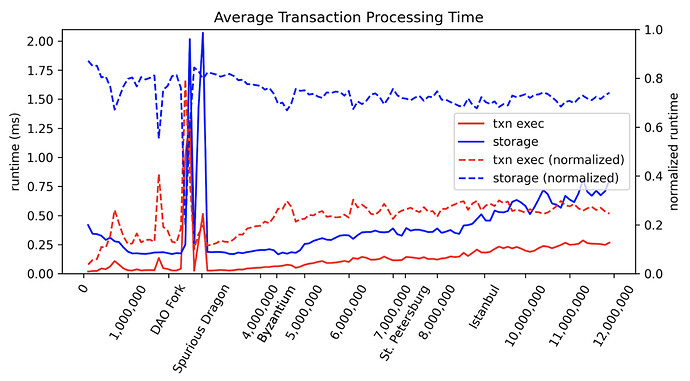

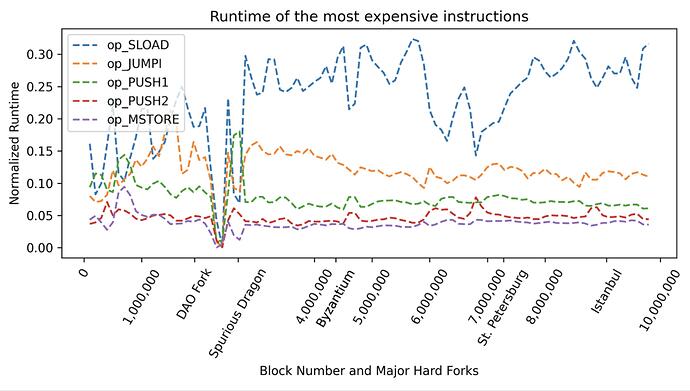

For node performances, EVM storage maintenance (manipulation of the Ethereum state Merkle trie) is the big bottleneck, which currently takes more than 70% of the transaction processing time. And for the other 20%+ part of actual EVM instruction interpretation time, the most time-consuming opcode is SLOAD because of the randomized access of Merkle trie nodes (so it cannot be efficiently cached) in a large database involving IO access.[3]

So, to scale Ethereum without compromising decentralization (i.e. without requiring nodes to have significant upfront cost like a powerful machine), what can we do?

Several directions have been proposed:

- Statelessness, which introduces a separation of roles within Ethereum nodes, with some nodes being “storage nodes” and others being “validator nodes.” The validator nodes will only receive part of the storage upon validating a block. The correctness of the storage is ensured by also transmitting a proof of its legitimacy. But this incurs extra network IO overhead. The solution is to use new data structures for Ethereum storage like Verkle trees to compress storage validation proofs.

- RainBlock, also a separation of node functionality proposal. Alongside storage nodes and validator nodes, it also introduces a special IO-helper node. This proposal runs into the same problem of incurring extra network IO overhead, and it tackles that problem with their custom data structure called DSM-tree.

- Sharding, which is analogous to a vertical separation of node functionality, offloads computation to different network segments.

These proposals, though promising, all involve significant changes to the underlying client or to consensus rules.

What we could do now, as an orthogonal direction, is to make the EVM parallel (i.e. executing transaction with no storage access conflicts at the same time, and maybe even pre-loading some storage accesses using optional access lists). This helps to directly increase EVM’s throughput so we could raise the gas limit and include more transactions in one block, raising the amount of transactions per second (tps). In addition, this can also horizontally help existing scalability proposals like sharding.

Efficient MEV Extraction

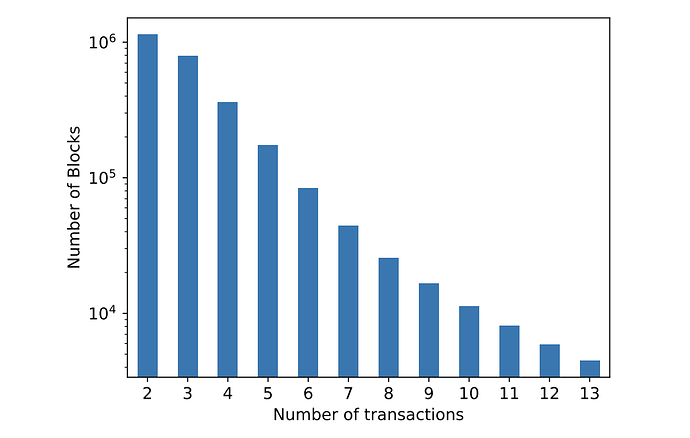

The following graph (taken from the Clockwork Finance paper from Babel et. al.) shows the number of blocks with more than one relevant AMM transaction that could be used for MEV extraction. The authors are only sampling deterministic single-block MEV opportunities before May 2021 from three DeFi protocols (MakerDAO, Uniswap, SushiSwap)[4], yet the result is striking.

Today, MEV opportunities are much more complex and typical validators (miners) see more than 10 MEV-emitting transactions per block.

Since block building and bundle profit optimization is an NP-complete problem, and we have so many MEV bundles to consider so that brute force is not realistic,[5] it is difficult for block builders to produce optimal full blocks efficiently (or, before the introduction of proposer builder separation, mega-bundles).

A study on EVM parallelization can help with this increasingly challenging bundle merging problem. As essentially, the dual problem of parallelization algorithm design is understanding how clashes take place in searcher bundles: they both require knowing a transaction’s shared data access information. Moreover, a parallel EVM helps full block builders (and MEV searchers) do more simulations, therefore producing more profitable bundles (as we previously mentioned, producing the most profitable block is an NPC problem, so an important way to be competitive and push the extraction limit is to do more state-space searches, i.e. simulations[6]).

A breakdown of the parallelization problem

Parallelizing the EVM might not be as simple as it seems. Naive solutions like speculative concurrency (optimistically execute transactions in parallel, then check for conflicts, if exists, resorts to sequential execution) have shown that the conflict rate for optimistic execution grows as Ethereum becomes more and more crowded (more transactions in mempool). Just for transactions in 2017, there is already a ~35% conflict rate.

The high conflict rate indicates that we need to devise a more refined parallelization algorithm, which will require more precise storage access information. Next, we scope these tasks formally.

Let the current blocknumber be k, the state of the Ethereum blockchain be s_k, and the state transition function of the sequential EVM be \delta(\bar{t}, s) which returns a new EVM state given a list of transactions \bar{t} and a state s. Suppose in list \bar{t} there are n transactions txn_1 to txn_n with an ordering of txn_1 \prec txn_2 \prec ... \prec txn_n (txn_i \prec txn_j means we only start executing txn_j after we finish executing txn_i).

Our goal is to devise a parallel EVM execution state transition function \delta_p such that \delta(\bar{t}, s_{k-1}) = \delta_p(\bar{t}, s_{k-1}). Note that in \delta always executes \bar{t} in the order they are passed in, while in \delta_p, \bar{t}'s execution isn’t ordered. For example, two transactions running on two different CPU cores could finish execution at the same time, or that txn_j's execute would finish before we start executing txn_i.

For us to derive a good \delta_p, we have two jobs:

- Derive information on possible shared data conflicts (this is where bundle clashing analysis could be informative) for each transaction.

This means that if we are only parallelizing at the transaction level, shared data conflict would be just the EVM storage since the only way in which info from one transaction can spill over to a different transaction is via storage. If we were parallelizing at deeper levels like EVM opcodes, then the information we derive would also include EVM stack and memory.

Formally, this means that with each txn_i, we have some information on its shared data access \kappa(txn_i). This information could be anything, for example, \kappa(txn_i) could return a set of storage location literals in the contract code that the transaction calls. Assuming the perfect information function is \kappa_{perfect}, then the \kappa we derive is an estimation of \kappa_{perfect}.

- Based on the preciseness of the information, we design our algorithm \delta_p(\bar{t}, s_{k-1}, \kappa) which now takes in \kappa as an additional parameter.

The exact strategy and abstraction level on which we parallelize depends on how refined \kappa is and to what degree we tolerate conflicts (similar to how sharding works). For example, with perfect information \kappa_{perfect} on each transaction’s calldata, stack, memory, and storage, we could design a \delta_p that parallelizes on the opcode level with no conflicts.

For simplicity, we only consider transaction-level parallelism in this post. That is, we assume \kappa only contains information on storage access. We leave the more refined parallelization models for future posts.

We realize that this formalization is different from what one would usually employ to implement a parallel EVM (instantiating multiple VM instances with read/write locks on the same storage database). The reason for us to choose such a formalization is that by separating \kappa, we can easily re-purpose the algorithm for optimizations like operation batching and caching[7].

Next, we discuss how to approach those two jobs respectively.

Storage access information (the first job)

To retrieve information on storage access, one could directly acquire that from manual input. For example, changing how transactions are passed in and require devs/users to list an overestimate of the addresses they are going to use, or like Solana or other UTXO-based chains, have every transaction include a list of account signatures that it interacts with. This seems like an easy solution because we incur no runtime overhead for the generation of \kappa (since it is provided like an oracle) and can always ensure its soundness (by reverting the transaction if it is not). But these methods require at least changing the client or implementing an additional layer before the client. Moreover, they change user/developer habits a lot, so it may be hard to enforce.

Alternatively, Ben Jones from Optimism proposed in a talk that we outsource the work to flashbots searchers as they need to simulate transactions any way when coming up with a profitable bundle.[8] This method achieves the best precision by providing \kappa = \kappa_{perfect}, but it relies on searchers to honestly pass additional information along with their bundles and only covers clients that use mev-geth. More importantly, it is hard to enforce in a permission-less system like flashbots without devising some additional incentive systems.

Another idea is to use speculatively generated storage information ahead of runtime and cache it[9] (kind of like how estimateGas works in most web3 libraries). Because this method is speculative, the storage information collected is unsound, in which case we fall back to normal storage access. This proposal works best if we have node functionality separation like in Rainblock (because it is offloading work to other VM instances). But as discussed previously that is assumed to be not present.

Another interesting idea is formal methods-aided bytecode analysis to achieve high-performing parallelization, which we will cover in the next post. One example of it is Forerunner, which achieves a 8x performance boost compared with raw geth, is also based on the idea of speculative execution and is most similar to our approach in the second post in that they also use formal methods techniques to aid the generation of \kappa.

Parallelization algorithms (the second job)

At this stage, we should have already acquired the necessary shared data access information \kappa using whatever method of our choice. Now, for demonstration purposes, we use a specific example of \kappa. Suppose we have two transactions txn_i \prec txn_j that both access a storage location \sigma, we record their access information as a tuple of tuples {(r, w), (r, w)}. The first tuple (r, w) denotes the read/write operation of txn_i and the second tuple denotes those of txn_j. For example, writing {(r), (r, w)} means that txn_i read but didn’t write to \sigma while txn_j both read and wrote to \sigma.[10]

Using this formalization, we can think of four simple situations:

-

{(r), (r)}: txn_i and txn_j are parallelizable, assuming that \sigma is only one in the “read” set of both those transactions. -

{(r), (w)}: txn_i and txn_j must be executed sequentially in order of \bar{t}. -

{(w), (r)}: txn_i and txn_j must be executed sequentially in order of \bar{t}. -

{(w), (w)}: if the write operation to s' is commutative (e.g. addition on unsigned integers is a commutative operation), then txn_i and txn_j are parallelizable, or else they must be executed in order of \bar{t}.[11]

However, txn_i and txn_j access not only \sigma but more locations, so we extend our four simple rules to include a read set and a write set for every transaction, and when searching for parallelizable transactions to execute, we loop through every transactions’ storage access information \kappa and apply the above rules.

Alternatively, we could use the simple algorithm described by Vitalik in EIP 648: each transaction includes a set \beta of the addresses it accesses, and if two transactions txn_i and txn_j satisfy \beta_i \cap \beta_j = \emptyset, then execute them in parallel, else not.

Ultimately, it all depends on how refined our \kappa is and how refined we want our parallel execution to be.[12] For example, it could be more than quadratic, meaning that we have \kappa not only contain storage access information but also those on memory/calldata, as we are parallelizing within a single transaction as well.

Of course, within those four situations, there are many complexities. For example: {(w), (w)}. In this situation, it is possible that we have txn_i first reads s' and then changes it, but the value assigned to s' always equals that of txn_j's assignment because of how the smart contract was written. So this effectively reduces to the {(r), (r)} case. Or this could easily go the other way and reduce to {(w), (r)}, {(w), (w)}, or {(r), (w)}. And even then it could be that the writer somehow doesn’t change the storage’s value or that the reader doesn’t affect state change in the EVM (e.g. reading some value to be 2 while it was originally 1, but the only use for that storage reading was only a require checking if the variable is positive).

The point of those examples is just to say that there are lots of specific classes of situations where our parallelization algorithm doesn’t work optimally.[13] So this means depending on the exact structure of \kappa, there are lots of long-tail optimizations for us to devise vastly different parallelization algorithms for optimal performance. We will come back to exact optimizations for this in the next post.

Conclusion

EVM parallelization facilitates Ethereum’s throughput increase without compromising on decentralization or requiring major changes to the protocol. The adoption and open sharing of research on parallel EVMs can also help to minimize economic centralization from MEV by allowing more individuals to use better bundle merging and production.

In this post, we explored the landscape of Ethereum scalability solutions and discussed why current parallelization tricks don’t work smoothly. We also presented our formalization of the parallelization problem by dissecting it into two parts: generating shared data access information and devising a parallelization algorithm that utilizes the information.

-

Even though at the moment the biggest bottleneck of Ethereum is not EVM’s performance (the size of the Ethereum state storage is), it will soon be as Ethereum TPS goes up. ↩︎

-

Of course, many other optimizations don’t need base layer changes, such as batching state read & write operations, caching, flattening the storage database, or just using a more performant programming language. We see many of those optimizations implemented in clients like Akula and Silkworm. We believe the content of this post (especially the part on shared data conflict analysis) should also help the aforementioned optimizations (e.g., through state preloading). ↩︎

-

SSTOREis not a big overhead because EVM inherently caches it and thus no expensive Merkle trie update is performed during runtime) ↩︎ -

For detailed benchmark setup, refer to the original paper at https://arxiv.org/pdf/2109.04347.pdf ↩︎

-

Default mev-geth release only merges 3 bundles per block, and over the past year on average there are 5 bundles per block, which is much less than the total number of profitable bundles per block. ↩︎

-

It is true that many traditionally discussed NP hard problems have very good approximation algorithms and we probably will see the same happen in the block building game: builders try to optimize for algorithmic heuristics (or network structures so they can see more searcher bundles and have lower propagation latency) more rather than putting all the effort into pure simulation speed. ↩︎

-

For example, if we use SGX as a future solution for MEV bundle privacy solution, then one major optimization is to use enclave memory as a cache for Ethereum storage data, which require us to have information on the bundle’s shared data access, i.e., \kappa. ↩︎

-

This is analogous to the Rainblock solution in which there is a separation of roles: searchers are acting as Rainblock’s “IO helper” nodes. ↩︎

-

Here we mean speculatively generating \kappa, not speculatively executing the transactions with read/write locks (which has a higher conflict rate and doesn’t achieve optimal scheduling). ↩︎

-

To audiences familiar with parallel programming, the description of parallelization algorithm here resembles the synchronization mechanism of (fine-grained) read-write locks. We deliberately chose this formulation over synchronization primitives to avoid getting into the details of data races. ↩︎

-

Examples of (non)commutative writes in smart contracts can be found here. ↩︎

-

Other blockchains such as Solana greedily (based on validator’s \kappa, which is the signed account addresses every transaction has in its signature) separate mempool transactions into different batches for parallel execution and use storage locks to prevent any potential data races. ↩︎

-

In fact, due to impossibility results, there will always be sub-optimal situations and it is impossible to eliminate them. ↩︎