Backrunning Private Transactions Using MPC

This article examines the use of secure multi-party computation in allowing searchers to backrun users’ transactions while preserving transaction and search strategy confidentiality.

Thanks to Alejo Salles, Jonathan Passerat-Palmbach, Mateusz Morusiewicz, Quintus Kilbourn, Alex Obadia, Chris Hager, Leonardo Arias, and Hasu for feedback and discussions. ![]()

Please find the proof-of-concept code for backrunning private transaction using MPC on GitHub. There is also a 20-minutes presentation, in case you prefer watching a presentation instead of or in addition to reading this article.

Introduction

Blockchains operate through the creation of blocks, which are published by proposers and consist of a list of user-generated transactions that are executed in order. However, the ability of proposers to alter the order of transactions and censor certain transactions has led to the rise of an MEV extraction industry. In this industry, users bleed money to searchers, builders, and proposers who specialize in extracting value, building profitable blocks, and earning fees for block inclusion. While some forms of MEV are widely seen as harmful to users, there is no widespread agreement on how to address it. Some efforts aim to mitigate MEV by using transaction ordering protocols or private mempools with threshold cryptography, for example, while others aim to reshape the value extraction industry such that it benefits users. The approach discussed in this article belongs to the latter category.

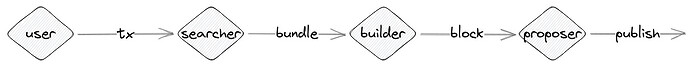

Illustration of the End-to-End Transaction Supply Chain

When examining the entire MEV transaction supply chain from user to proposer, it becomes clear that solving MEV in this model - where nobody gets any feedback until the block lands on chain - at once is overly complicated. In this article, we focus on the user-searcher interface, where the user wants to keep their transaction confidential from the searcher and also the searcher wants to keep their search strategy confidential from the user as well as the builder. The approach described in this article allows for both front-running and backrunning of transactions. While front-running and some other forms of value extraction are considered harmful to users, backrunning allows for efficient arbitrage and liquidations without impacting users since their transaction have already been completed. However, searchers competing over backrunning opportunities in the public mempool have led to negative side effects, such as bidding up transaction fees and making transactions more expensive for all users. Therefore, there is a need for a solution that allows searchers to backrun users’ transactions without negatively affecting everyone, with privacy being the core of such a solution.

In order to make the problem more tangible, we simplify it further by considering a scenario with only one user and one searcher, who send the backrun transaction to a single builder who is trusted to not extract value from the user’s transaction and to include both the user’s transaction and the searcher’s signed backrun transaction in the same block.

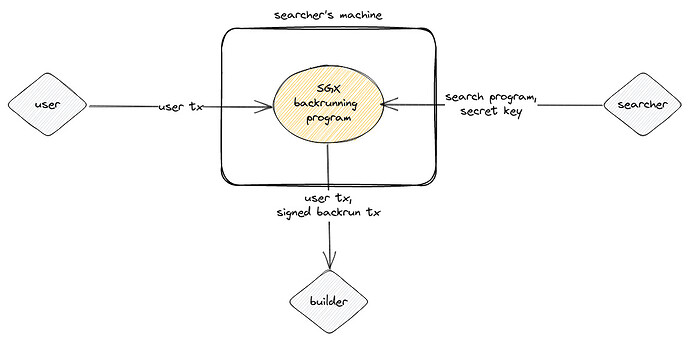

SGX-Based Backrunning and Covert Channels

Given this private computation setting, Trusted Execution Environments (TEEs) such as Intel’s Software Guard Extensions (SGX) come to mind as a reasonable solution. The purpose of Intel’s SGX is to provide secure remote computation, meaning that the correctness of an output of a trusted program can be assured even if it was executed on an untrusted machine.

SGX-based Backrunning Private Transactions

An SGX-based solution for backrunning private transactions could involve the following steps:

- The user submits a transaction to the backrunning program, which operates within an SGX enclave on the searcher’s machine.

- The searcher provides a search program and a secret key to the backrunning program.

- The backrunning program is executed within the SGX enclave and uses the search program to generate a backrun transaction from the user’s transaction.

- The backrun transaction is then signed with the secret key provided by the searcher.

- Finally, both the user’s transaction and the signed backrun transaction are sent to the builder.

It’s important to note that all communication between the SGX backrunning program and all entities can be transport-layer encrypted.

backrun_tx = SEARCH_PROGRAM(USER_TX)

signature = sign(backrun_tx, SECRET_KEY)

sendToBuilder(USER_TX, backrun_tx | signature)

However, there is an issue: covert channels. Covert channels are a method of secretly conveying information by piggybacking on existing overt channels that are misused to exfiltrate information. Another way to think of covert channels is as a way of secretly modulating information on an existing carrier signal. Covert channels differ from side channels in that a side channel attack allows an attacker to observe the system only from the outside, while a covert channel attack allows an attacker to get support from inside the system. The concern is that (untrusted) inputs can potentially alter program execution in such a way that secret information is leaked through covert channels. In the case at hand, the searcher program may be used to alter the execution of the SGX backrunning program such that the user’s transaction is revealed. To prevent this, it’s crucial to examine the specific overt channels in place.

| Existing Overt Channel | Countermeasure |

|---|---|

| Enclave’s output, i.e., a bundle |

|

| Network communication |

|

| CPU and memory of the host system | ⁇ |

Since the user’s transaction is already part of the enclave’s output, the output has to be (transport-)encrypted. Otherwise, the searcher could just observe the output and learn the user’s transaction this way. Another way to exfiltrate information is through network communication, which must be restricted to avoid this information leakage. This means that connecting to the Ethereum P2P network is not possible, as each connection and each query can be used to exfiltrate information. Two other overt channels to consider are the CPU and memory of the host system. For example, a covert channel could encode information through the CPU by using high or low CPU usage to represent binary values. Another covert channel could encode information through the allocation of memory pages or patterns of memory access.

To ensure the user’s transaction remains confidential, the searcher’s input must not be able to alter program execution in a way that reveals the transaction through covert channels. Restricting the expressiveness of the searcher’s input seems to be a prerequisite, but this may not be desirable for the searcher. For this reason, there exists a trade-off between the expressiveness of the searcher’s program and the potential for covert channels. It can be challenging to determine the right balance and starting point, as the design space is vast. One approach could be to start fully expressive and gradually restrict the expressiveness until the amount of leaked data is deemed reasonable, but it may be difficult to determine this with certainty. Another approach could be to start fully restricted and gradually loosen restrictions until the searcher’s program is expressive enough, but it’s unclear how to determine when this has been achieved. Alternatively, starting somewhere in the middle of the expressiveness-covert channels trade-off space may be a blind approach.

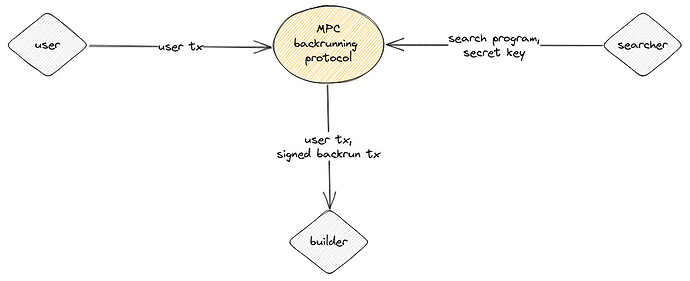

MPC-Based Backrunning

To explore the design space of search program’s expressiveness, without leaking information through covert channels, we use secure multiparty computation (MPC). MPC enables multiple parties to jointly compute a public function while keeping their inputs confidential, ensuring that only the output of the function is revealed. One commonly used technique for achieving this is Shamir secret sharing, where inputs are divided into shares, distributed among the parties, and computations on the shares are performed without revealing the actual input values.

MPC-based Backrunning Private Transactions

In our design, we use MPC to ensure that the builder, who is trusted not to extract value, is the only party receiving the user transaction and signed backrun transaction output, thereby eliminating the potential for covert channel exploitation. The MPC setting is similar to that of SGX, but with two key differences. First, the backrunning program is executed as a communication protocol between the user and the searcher, rather than as a program within an SGX enclave on the searcher’s machine. Second, confidentiality is ensured through MPC instead of SGX.

By using MPC, we can explore the design space of the search program’s design space securely, without the risk of information leakage through covert channels. The inputs to the function are kept confidential through the use of cryptographic techniques, ensuring that only the output of the function is revealed. We experimented with MP-SPDZ, a general MPC framework, to design the searcher language and the backrunning protocol.

It’s important to stress that our goal at this point is to open the space for exploration and not create a practical solution. To this end, we rely on abstract concepts such as MPC, which can be implemented using various techniques like Shamir secret sharing, to achieve confidentiality and security in the design process.

The user inputs a complete transaction into the MPC backrunning protocol, while the searcher inputs a searcher program that represents their strategy, as well as a secret key to sign the backrunning transaction. The MPC backrunning protocol then creates a backrunning transaction based on these inputs. The searcher program consists of four parts, which are executed in that order:

- A list of constants.

- A list of basic computing instructions, formatted as

<operand1_location><operator><operand2_location>, where the location refers to the location of the operand in the protocol’s internal storage. The storage is populated with data from the RLP-decoded user’s transaction and searcher-provided constants. The result of a computation is appended to the protocol’s internal storage, which allows operations to use results from previous computations. The PoC supports basic arithmetic operations such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, division, and square root. Loops with a length dependent on secret information are not permitted, as they would lead to information leakage. Fixed-length loops, yet, can be supported by unrolling the loop. - A set of basic comparison instructions in the format of

<comperand1_location><comperator><comperand2_location>. The location refers to a location of the comperand in the protocol’s internal storage. The PoC currently supports the following comparisons: less than, less than or equal, greater than, greater than or equal, equal, and not equal. - A list of references to populate the backrunning transaction. The first item refers to the protocol-internal storage location of the nonce, the second item refers to the storage location of the gas limit, the third to the gas price, and so forth.

Now that we described the searcher language, which defines the structure of a search program, let’s examine the design of the MPC backrunning protocol:

# protocol-internal storage

storage = []

# RLP-decode the user's transaction and append to storage

storage.append(RLPDecode(TX))

# append searcher-provided constants to storage

storage.append(SEARCHER_PROGRAM.constants)

# execute searcher-provided computations on storage

for p in SEARCHER_PROGRAM.computations:

execute(p, storage)

# perform searcher-provided comparisons on storage and track whether all returned True

success = True

for c in SEARCHER_PROGRAM.comparisons:

success &= perform(c, storage)

# create backrunning transaction

backrun_tx_unsigned = RLPEncode(propagateTx(SEARCHER_PROGRAM.references, storage))

# sign backrunning transaction

backrun_tx_signed = sign(backrun_tx_unsigned, SECRET_KEY)

# send user transaction and signed backrunning (or empty) transaction to builder

if success:

sendToBuilder(TX, backrun_tx_signed)

else:

sendToBuilder(TX, None)

Proof-of-Concept Walk-Through

This section goes into the technical details of the implementation. While not required to understand the high-level design, it may still be of interest for those who want to gain a deeper understanding. If you prefer to just get a general idea, feel free to skim this section and proceed to the open questions and conclusion of this article. For those who would like to see the specifics, we’ve included a step-by-step example. The proof of concept was implemented using MP-SPDZ, which has a syntax similar to Python. The code and instructions on how to set up and run the code can be found on GitHub.

The PoC code has the following limitations:

- Signature generation for the backrunning transaction is not included in this PoC. Although the implementation of signature generation would be beneficial for the PoC, it is not considered the highest priority in light of the goal to explore the trade-off between the expressiveness of the searcher’s program and the potential for covert channels.

- The originator of the transaction is not extracted, which could be used for searching and for paying rewards.

To demonstrate the PoC, we use a real-world transaction from December 2022 in which 3.75 ETH were exchanged for 4,784.912579 USDT on Uniswap V2: https://etherscan.io/tx/0xe31ba3d6c9a0a87730a6d49565f7d445aa7240ae823758ee74f4d4f76fdc9f28.

The MPC backrunning protocol consists of the following steps:

- Decode the user’s transaction using RLP and populate the protocol-internal storage.

- Load constants from the searcher program and add them to the storage.

- Execute computations from the searcher program.

- Perform comparisons from the searcher program.

- Create the backrunning transaction.

Decoding the Transaction with RLP

The protocol begins by decoding the raw user transaction and populating the storage. The internal storage then looks like this:

| Storage Slot | Value | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 3 | Nonce |

| 1 | 12000000000 | Gas Limit |

| 2 | 187657 | Gas Price |

| 3 | 0x7a250d5630b4cf539739df2c5dacb4c659f2488d | To-Address |

| 4 | 3750000000000000000 | Value |

| 5 | 0x7ff36ab5 | Data: Function Selector |

| 6 | 4761107043 | Data: amountOutMin |

| 7 | 128 | Data: address[ ] Offset |

| 8 | 0xb3d8374bda9b975beefde96498fd371b484bdc0d | Data: To-Address |

| 9 | 1669877861 | Data: Deadline |

| 10 | 2 | Data: address[ ] Length |

| 11 | 0xc02aaa39b223fe8d0a0e5c4f27ead9083c756cc2 | Data: Token1 |

| 12 | 0xdac17f958d2ee523a2206206994597c13d831ec7 | Data: Token2 |

Loading Constants

The next step involves loading the constants from the search program. It’s important to note that some provided constants represent on-chain information, such as the number of tokens in the ETH/USDT pool at block 16088213. This eliminates the need for the protocol to query the EVM state. However, it is the responsibility of the searcher to keep these constants updated as the EVM state changes.

| Comparison Data | Comments |

|---|---|

| 0x7a250d5630b4cf539739df2c5dacb4c659f2488d | Uniswap v2 Router Address |

| 0x7ff36ab5 | Function Selector swapExactETHForTokens(uint256,address[ ],address,uint256) |

| 2 | Path Length |

| 0xc02aaa39b223fe8d0a0e5c4f27ead9083c756cc2 | WETH Token Address |

| 0xdac17f958d2ee523a2206206994597c13d831ec7 | USDT Token Address |

| 1669870000 | Minimum Deadline |

| Constants for Backrunning Amount & Profit | |

| 3 | 0.3% Fixed Uniswap v2 Fee Dividend |

| 1000 | 0.3% Fixed Uniswap v2 Fee Divisor |

| 11866579405959229103761 | WETH in the Pool (at Block 16088213): 11866.579405959229103761 |

| 15191824718342 | USDT in the Pool (at Block 16088213): 15191824.718342 |

| 1000000000000000000 | WETH Precision |

| 2 | Constant for Computing amountIn (Backrunning) |

| 1283500000 | Maximum Buy Price (ETH/USDT Target Price for Backrun): 1283.5 USDT |

| 4 | Constant for Computing amountIn (Backrunning) |

| 1286000000 | Minimum Sell Price (ETH/USDT Target Price for Backrun): 1286.0 USDT |

| 2000000 | Cost of Arbitrage Execution: 2.0 USDT |

| 0 | Minimum Amount and Profit Requirements |

| Backrunning Transaction Data | |

| 101 | Backrunning Transaction Nonce |

| 12000000000 | Gas Limit |

| 187788 | Gas Price |

| 0x18cbafe5 | Function Selector: swapExactTokensForETH(uint256,uint256,address[ |

| ],address,uint256) | |

| 160 | address[ ] Data Offset |

| 0x4eed8f7a1df19a7fb7cc99b18909d99d065544b2 | ETH Recipient |

| 1669877869 | Deadline |

The necessary constant values have been added to the protocol-internal storage.

Execute Computations

Before delving into the computations executed in the search strategy, let’s clarify what the searcher aims to achieve and how the Uniswap v2 pricing function works. Uniswap v2 defines the price of an asset as the ratio of the number of tokens of the corresponding assets in the pool, X and Y, i.e., USDT and WETH. However, users do not get this price exactly, as they also incur a fixed fee of 0.3% when buying or selling an asset. This fee causes users to pay a slightly higher price when buying an asset and receive a slightly lower price when selling an asset. By trading, the number of tokens in the pool changes, and therefore, the price changes as well. To calculate the new number of tokens in the pool, we use the following formulas: X_\text{after} = X + \text{amount} and Y_\text{after} = \frac{X \cdot Y}{X + \text{amount} \cdot (1 - \text{FEE})}. Here, \text{amount} represents the number of X tokens that are sold for Y tokens. After the trade, the user receives Y - Y_\text{after} tokens of the Y asset. We can compute the price after the trade as

If we transform this equation to be expressed in the amount of tokens to be sold, and account for the difference in precision between USDT and WETH, we get:

So, why would the searcher need this equation? Suppose the price in the Uniswap v2 pool is changed by a trade in a way that makes it now profitable to arbitrage against another exchange, such as a centralized exchange (CEX). In that case, the searcher can use that formula to determine the amount of (USDT) tokens to sell to receive the maximum number of (ETH) tokens up to the target price. This is precisely what the formula accomplishes.

To execute a backrun of a swap of ETH for USDT on Uniswap v2, the searcher’s strategy should consider the market price on the CEX, the pricing function of Uniswap v2, and the state of the Uniswap v2 pool. In this way, the searcher can determine the amount of tokens they can buy up to a specific target price and calculate their profit. To compute the amount of USDT tokens to sell in the backrunning transaction, the searcher applies the previous formula, where X and Y are computed from the amount of WETH and USDT in the Uniswap v2 pool before and after the user’s trade. The constants FEE, PRICE, and PRECISION are provided by the searcher.

| Variable | Comment | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| X | The amount of USDT in the Uniswap v2 pool after the user’s trade. | X = \frac{\text{ETH}_\text{before} \cdot \text{USDT}_\text{before}}{Y} |

| Y | The amount of ETH in the Uniswap v2 pool after the user’s trade. | Y = \text{ETH}_\text{before} + \text{amount} \cdot (1 - \text{FEE}) |

| FEE | The fee for trading in Uniswap v2. | searcher-provided constant |

| PRICE | The price up to which to buy the asset. | searcher-provided constant |

| PREC | The number of decimals for WETH. | searcher-provided constant |

The profit is calculated as \text{profit} = (\text{sell price} - \text{buy price}) \cdot \text{amountOut} - \text{cost}, where sell price is the lower bound of the price at which the searcher can sell ETH at the CEX, buy price is the price up to which the searcher buys ETH for USDT on Uniswap v2, amountOut is the amount of ETH received from the backrunning transaction on Uniswap v2, and cost is the cost of executing both the on-chain transaction and the trade on the CEX. Although the formulas may appear daunting at first, the complexity mainly stems from understanding how the pricing function in Uniswap v2 affects the calculation of a backrunning transaction. All computations required are basic arithmetic operations (plus the square root function), and all necessary information is provided upfront or can be derived from the user transaction and searcher-provided constants. The computations are expressed in low-level code, with no variables, loops, nor branching, but only references to storage locations and operators. The operator codes are 0 for addition, 1 for subtraction, 2 for multiplication, 3 for division, and 4 for square root. Since MPC works on integers, operator names are considered part of a high-level language in future work.

# note that the fee in Uniswap is calculated as if it was taken from amountIn (although it is actually deducted from amountOut)

4 2 29 # amount paid to uniswap for fees = amountIn * fee = 3750000000000000000 * 3 / 1000

53 3 30 # division for the above

4 1 54 # amountIn_fees = amountIn - fees

31 0 55 # WETH in the pool after the swap (just for fee calculation - not for real) = WETH_before + amountIn_fees

31 2 32 # USDT in the pool after the swap = WETH_before * USDT_before / WETH_after

57 3 56 # division for the above (= Y)

31 0 4 # WETH in the pool after the swap, for real = WETH_before + amountIn (= X)

# below here are computations to calculate the amount for the backrunning tx

33 2 58 # VAR1 = PRECISION * X

35 2 29 # PRICE * fee (*3 of the fee part)

561 3 30 # PRICE * fee (division for the above (/1000 for the fee part))

35 1 562 # PRICE_FEES = PRICE - PRICE * fee

63 2 59 # VAR2 = PRICE_FEES * Y

34 2 33 # VAR3 = 2 * PRECISION

36 2 64 # VAR4 = 4 * VAR3

60 2 29 # (VAR5) = VAR1 * FEE (*3 of the fee part)

67 3 30 # VAR5 division for the above (/1000 for the fee part)

60 2 66 # VAR6 = VAR1 * VAR4

68 2 68 # VAR5 * VAR5

69 2 29 # VAR6 * FEE (*3 of the fee part)

71 3 30 # VAR6 * FEE division for the above (/1000 for the fee part)

70 1 72 # VAR5 * VAR5 - VAR6 * FEE

73 0 69 # above + VAR6

74 4 0 # sqrt(). second operand is unused.

75 0 68 # sqrt() + VAR5

34 2 60 # 2 * VAR1

76 1 77 # sqrt() + VAR5 - 2 * VAR1

# dividend done

65 2 29 # VAR3 * FEE (*3 of the fee part)

79 3 30 # VAR3 * FEE division for the above (/1000 for the fee part)

65 1 80 # VAR3 - VAR3 * FEE (= divisor)

78 3 81 # amount = dividend / divisor

# finished computing the amount for backrunning here

# profit = (sell price - buy price) * amountOut / PRECISION - cost

# amountIn now refers to the amount of the backrunning tx.

82 2 29 # amountIn * FEE (*3 of the fee part)

83 3 30 # amountIn * FEE (division for the above (/1000 for the fee part))

58 0 82 # X + amountIn

85 1 84 # X_after_fee = X + amountIn - amountIn * FEE

58 2 59 # X * Y

87 3 86 # Y_after = X * Y / X_after_fee

59 1 88 # amountOut = Y - Y_after

37 1 35 # sell price - buy price

90 2 89 # (sell price - buy price) * amountOut

91 3 33 # (sell price - buy price) * amountOut / PRECISION

92 1 38 # profit = (sell price - buy price) * amountOut / PRECISION - cost

# profit done

Perform Comparisons to Validate the Transaction

The searcher wants to ensure that the backrunning transaction is sent to the builder if and only if the user’s transaction indeed swaps of ETH for USDT on Uniswap v2 and the backrunning transaction is indeed profitable. To this end, the searcher performs comparisons in order to validate the user’s transaction as well as the results of the computation in the previous step of the MPC backrunning protocol. Note that this low-level representation only references storage locations and comparators. The comparator codes are 5 for less than, 6 for less than or equal, 7 for greater than, 8 for greater than or equal, 9 for equality, and 10 inequality.

3 9 23 # to address == Uniswap V2 router

5 9 24 # function selector/method id == swapExactETHForTokens(uint256,address[],address,uint256)

10 9 25 # path length == 2

11 9 26 # token1 == WETH

12 9 27 # token2 == USDT

9 8 28 # deadline >= minimum deadline

82 7 39 # backrun amountIn > 0

93 7 39 # backrun profit > 0

Generating the Backrunning Transaction

The creation of the backrunning transaction only involves a list of references to the locations of protocol-internal storage items and encoding them using RLP. In this PoC, the searcher utilizes the same Uniswap v2 pool for the backrunning transaction, but calls the swapExactTokensForETH function instead of the swapExactETHForTokens used by the user. By inputting USDT, the searcher will receive ETH that can be sold for profit.

40 # nonce

41 # gas limit

42 # gas price

23 # to address. Uniswap v2 router

39 # value. 0

43 # function selector/method id for swapExactTokensForETH(uint256,uint256,address[],address,uint256)

82 # amountIn

89 # amountOutMin == amountOut

44 # storage location

45 # to address. recipient of the ETH

46 # deadline

25 # len of address[]/path

27 # token1. USDT

26 # token2. WETH

Results of Backrunning the Swap

At block 16088213, the Uniswap v2 pool held approximately 11,866.58 WETH and 15,191,824.72 USDT. Our in-protocol computations were consistent with the on-chain state of the pool at block 16088214, which showed approximately 11,870.33 WETH and 15,187,039.81 USDT. The price of 1 WETH before the swap was around 1,280.22 USDT, while after the swap, it was around 1,279.41 USDT.

In this PoC, the searcher was willing to pay up to 1,283.5 USDT per WETH and purchased approximately 1.1008 WETH for approximately 1,412.70 USDT (at a price of about 1,283.38 USDT/WETH). The searcher also specified that they could sell ETH for at least 1,286.0 USDT on a CEX, with a 2.0 USDT cost (including the cost for the backrun).

Based in this information, the backrun generated a profit of at least 0.75 USDT. However, if the searcher had specified that they could only sell ETH at a lower price or that the cost of selling ETH plus the backrun would be higher, the backrun transaction would not have been profitable and therefore not have been generated.

Open Questions and Future Work

- Expressiveness of the searcher language: The searcher language’s current functionality can be extended by incorporating more operators such as modulo or shifting. Nevertheless, it is unknown if the language is indeed expressive enough to implement all the existing search strategies.

- Improving the usability of the searcher language: The current searcher language is low-level and prone to errors. One way to address this is to create a high-level language that compiles to the low-level searcher language. The high-level language could include features such as variable names, operator names, comments, fixed-length loops, and the ability to perform multiple operations within a single expression. What could such a high-level language look like in detail, and what additional features could it offer? Would the support of branching in the computational step be useful?

- Making the PoC practical: The current MPC backrunning protocol has excessive computational and communication overhead, rendering it impractical for real-world use. For example, in the strongest MPC security model, where two of the three parties can act arbitrarily malicious while retaining information secrecy, execution takes approximately 22.5 hours and requires 33.7 PB of data transfer across 9.6 million communication rounds. Even in the weaker security model used for testing, where two parties are assumed to be honest, and the third party attempts to extract as much information as possible without deviating from the protocol, execution still takes around 4 minutes and requires 6 GB of data transfer in 3.5 million communication rounds. While the focus of this PoC was to examine the trade-off between the expressiveness of the searcher’s program and potential covert channels—not performance optimization—the critical question remains: how can the searcher language and the backrunning protocol be implemented practically for real-world use? Several possible solutions seem conceivable, such as implementing the searcher language and the backrunning protocol with SGX, transforming the three-party MPC setting into 2PC with garbled circuits, or using homomorphic encryption instead of, or in addition to, MPC. By exploring these options, our goal is to make the searcher language and the backrunning protocol more practical for real-world use.

Conclusion

This article examines the user-searcher interface in the MEV transaction supply chain, focusing on the confidentiality of both the user’s transaction and the searcher’s strategy, while enabling searchers to perform backrun transactions. The use of SGX is discussed, and covert channels are identified as a threat to the confidentiality of the user’s transaction. We explore the balance between the expressiveness of the searcher’s program and the risk of information leakage through covert channels. To address this challenge, a backrun protocol and a covert channel-free searcher language are developed, using MPC. Finally, we demonstrate a proof-of-concept backrun implementation on a Uniswap trade.

With that, thanks for reading, and looking forward to your comments! ![]()

![]()